Expedia has stated on many occasions that the recent movement of large hotel chains offering the best direct price is detrimental to the hoteliers themselves. We do not share their vision and here is why.

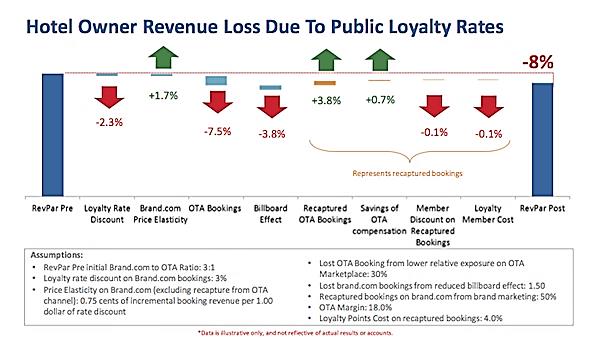

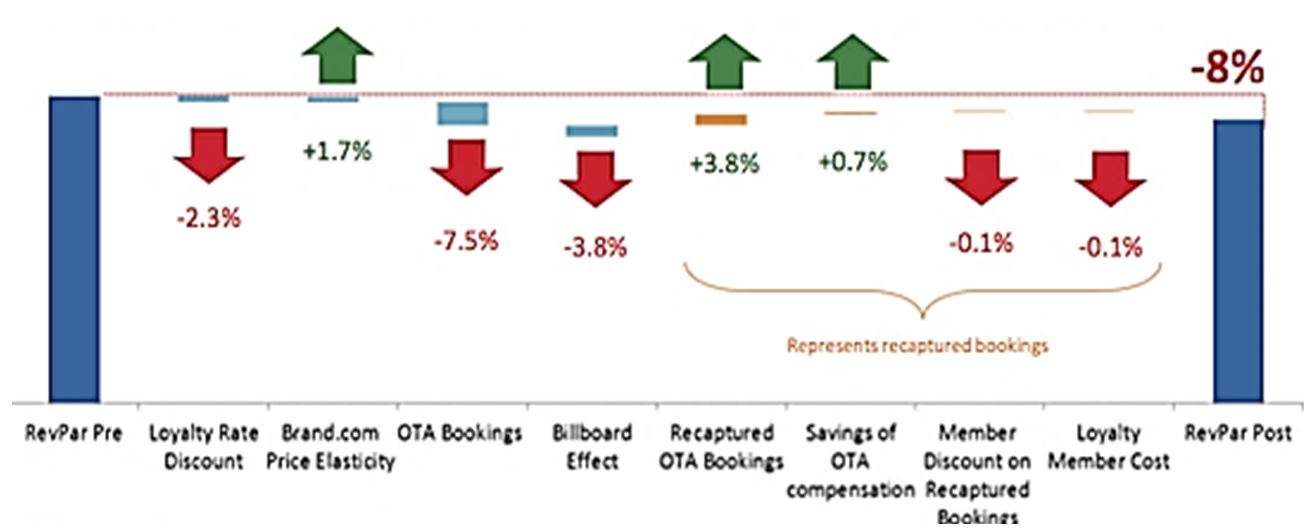

In April, Skift published this interesting and complex graph with which Expedia allegedly proved an 8% decrease in the hotel’s net RevPAR.

In the supposed starting scenario, the hotel/chain’s website (Brand.com) sells three times more than OTAs. This ratio varies from one hotel to the other and the final result would be affected subject to each ratio.  We accept Expedia’s 3:1 scenario. It’s important to remember this proportion to understand the calculations: 75% website – 25% OTA. This ratio, albeit unrealistic in Europe, seems reasonable for the large American hotel chains it’s directed towards.

We accept Expedia’s 3:1 scenario. It’s important to remember this proportion to understand the calculations: 75% website – 25% OTA. This ratio, albeit unrealistic in Europe, seems reasonable for the large American hotel chains it’s directed towards.

Expedia posed an apparently correct mathematical analysis and almost all variables were considered, but the numbers are based on unrealistic assumptions. Let’s analyse them.

-

The discount on the hotel’s website (Brand.com) would have a negative effect on the net RevPAR

According to Expedia: -2.3% RevPAR

Expedia estimates the average discount on a hotel website to be of 3%. (« Loyalty rate discount on Brand.com bookings: 3% »)

Like all price decreases, it has a negative effect on the RevPAR.

-3% x 75% = 2.3%

(-2.3% is the result of applying -3% on the hotel-website sales which, remember, represent 75%)

According to Mirai: 0%

Apparently correct yet too simplistic. If every new discount on a channel meant that the hotel lost money, the industry would be in disarray after years of seemingly omnipresent discounts in all distributors. In practice, the hotel can make up for one-off price decreases with general increases in reference prices.

Furthermore, if we talk about prices, there is an effect overlooked by Expedia: the packages discount, which only exists in OTAs. The fewer OTA bookings there are, the fewer bookings with that discount there will be and therefore there will be a higher average price and RevPAR.

At Mirai, we believe that the hotel can have sufficient control over the average general price in order for this point to affect the net RevPAR: neither by offering a direct discount nor by reducing the Expedia-package discount. In other words, a one-off variation of conditions in a channel has a one-off effect on that particular channel but that can be offset on the remainder of channels in order not to affect the overall result.

-

The discount would increase the number of bookings on the hotel’s website thanks to the elasticity of the demand

According to Expedia: +1.7% RevPAR

Levels of demand would react positively to the decrease in prices, something which would translate into an increase in bookings. Expedia locates this elasticity in an increase of $0.75 in new bookings for each discount point. In other words, it would not make up for the loss from the discount. (« Price Elasticity on Brand.com -excluding recapture from OTA channel-: 0.75 cents of incremental booking revenue per 1.00 dollar of rate discount »)

0.75 x 3 x 75% = 1.7%

(If each dollar discounted results in an increase of 0.75 in income, a discount of 3% on 75% of the bookings would result in +1.7% of income)

According to Mirai: 0%

Since we believe that there is no reason to vary the average price of the hotel, there will be no reaction to the demand and no new bookings will exist.

-

Decrease in bookings by OTAs due to loss of ranking visibility. Negative effect on net RevPAR.

According to Expedia: -7,5% RevPAR

OTA bookings would decrease by 30% as a direct consequence of a lower hotel exposure. (“Lost OTA booking from lower relative exposure on OTA Marketplace”)

-30% x 25% = -7.5%

(Losing 30% of a channel that represents 25% means losing 7.5%)

According to Mirai: -7,5%

This is the point that Expedia gives the most importance to. We accept their number but for a different reason to theirs. For us, the decrease in bookings is not caused by the OTA’s loss of ranking visibility. Different reasons explain this:

- Expedia backed out: At the time of publishing their study, Expedia punished rebel hotels by dimming their results. However, soon after they backed out and abandoned the punishment.

- Most users filter or order results, lessening the importance of the default ranking proposed by the OTA. (Booking.com published the number: Only “15% or so of the people go into a search result and only look at the search result as-is”)

- Part of OTA visitors search for the hotel’s name. They are also not affected by the default ranking of the destination.

- The largest loss in bookings comes from the decrease in CONVERSION, not visibility. Half of the hotel visitors on the OTA then go on the hotel’s website (Expedia say it themselves in the following point and it coincides with our data).

When visitors view the OTA and compare it to the hotel’s website, which offers a better price,

Where will they book?

Will there be a decrease in OTA bookings? Yes.

Will there be a decrease in views of the hotel’s page on the OTA? No

We accept the decrease in bookings and a hit of -7,5% on the RevPAR, although it is not caused by the decrease in visibility of the OTA.

-

With decreased visibility on the OTA there will be a lower billboard effect and less bookings on the hotel website

According to Expedia: -3.8% RevPAR

Each booking by the OTA generates 0.5 direct bookings. By reducing OTA bookings by 30%, the equivalent of half of those would be lost on the hotel website (“Lost brand.com bookings from reduced billboard effect 1:50”)

– 30% x 25% x 0.5= -3.8%

(Losing 30% on the OTA, which represents 25% of the RevPAR, will result in the loss of half that amount on the hotel website)

According to Mirai: There is no decrease in visibility, we ruled it out in the previous point. Therefore, there is no decrease in the billboard effect.

The assumption that every two bookings generate a direct booking is unreasonable. Yes, Google published that 52% of travellers visited the hotel website after seeing it in an OTA. Expedia probably bases its statement on this study. However, there are many other reasons that put this proportion into question:

- Correlation does not imply causality. Travellers compare a lot, up to 38 times on average on multiple channels. The attribution is complicated. To assume in a simplistic way that, in the booking process, passing through one channel implies booking on the following one is bold to say the least.

- And the OPPOSITE billboard effect? How many visitors of the hotel website then visit the OTA? Even if it was a lower proportion, it would be made up for by the larger base of the hotel website in comparison with the OTA. Remember, 3:1 in this scenario.

- A few years ago, Cornell University estimated that the billboard effect of hotel-website bookings lies between 7.5% and 26%, far from the 50% stated by Expedia.

- Wihp estimated the number to be 16% in 2014.

- A subsequent study believed the billboard effect to be obsolete.

- The Barcelona Hotels Association publishes the sales channels of its city’s hotels. In the latest survey, OTAs represent 50% of the total amount. If we go by Expedia’s logic, at least half of that 50% should come from hotel websites due to the billboard effect (if they only lived off the billboard effect). Actually, the percentage of direct website sales in the city is of 14.8%.

We therefore do not accept that there is any impact on the RevPAR due to this point.

-

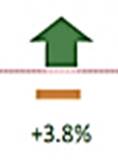

The hotel would make up for part of the losses with new direct sales

According to Expedia: +3.8% RevPAR

In order to find new clients, the hotel must make marketing investments for an amount equivalent to the OTA commission. The hotel could aspire to make up for 50% of its losses from the OTA. (« Recaptured bookings on brand.com from brand marketing: 50% »).

30% x 25% x 50%= 3.8%

(the loss of 30% of a channel that represents 25% could be compensated by 50%)

According to Mirai: +7.5%

It’s not about the hotel website finding NEW clients, but rather that clients who compare the OTA with the hotel website now choose to book through the latter. No clients or views are lost and therefore there is nothing that needs reinvesting.

The hotel website could aspire to receive 100% of the bookings lost by OTAs.

-

Saving on OTA commissions

According to Expedia: +0.7% RevPAR

With a commission of 18% (« OTA Margin: 18% »), the impact on the RevPAR would be of +0.7%.

30% x 25% x 18% x50% = 0.7%

(a 30% decrease on OTA bookings, which represent 25% of the total, with a commission of 18% and counting just half*)

*Half because the hotel cannot keep it all. It would have to use that amount for reinvestment in order to recover direct sales – see following point.

According to Mirai: +1.4%

The hotel will keep the full amount of the commissions of the bookings moved to the hotel website, not just half.

- Visitors “gifted” to the hotel website: marketing cost = 0. According to Expedia, half of its users will visit the hotel website and book on it. We have already said that views will not decrease. What will change is that they will now find a better price and therefore their conversion will increase. Not only will they book more on the website but also the hotelier will not pay commission on these bookings nor will he have to pay marketing costs to get them.

- Visitors that the hotel website sends to the OTA and will no longer convert to it having seen its higher price. In other words, a reverse billboard effect. Not only will this produce more bookings on the hotel website but it will also do so at a lower cost.

With 18% commission, the saving because the OTA (which represents a quarter of the bookings) sells 30% less, it results in an impact on the RevPAR of +3,1%

As a curiosity, Expedia has used a commission rate of 18%. Each hotelier will know whether it coincides with what they pay, including the higher commission for packages. Those who pay more will find out that:

- They will save even more

- They are paying more than most hotels

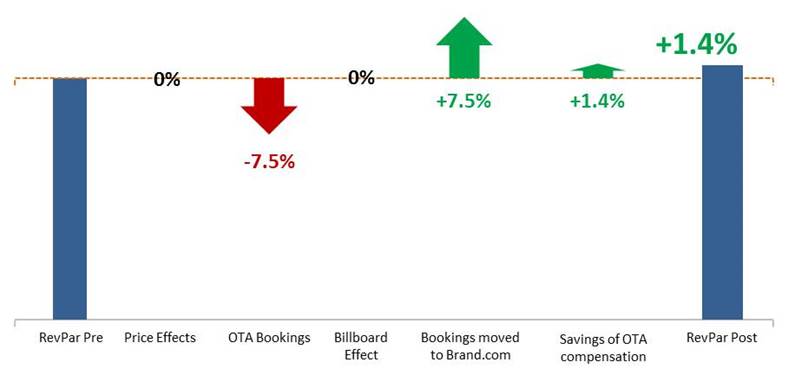

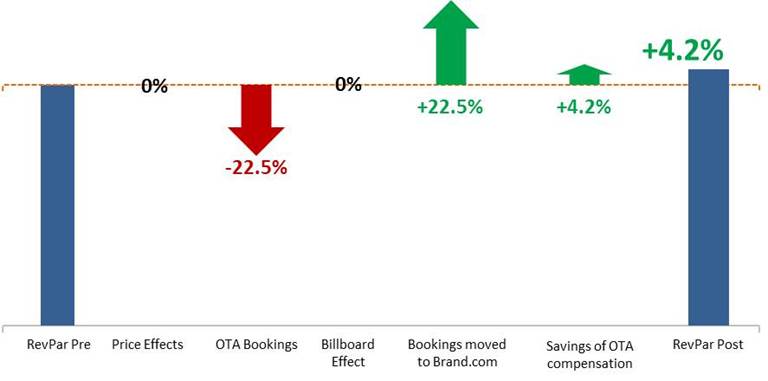

Assessment of the scenario in which the hotel website sells three times more than the OTA

According to Expedia: -8%

According to Mirai: +1,4%

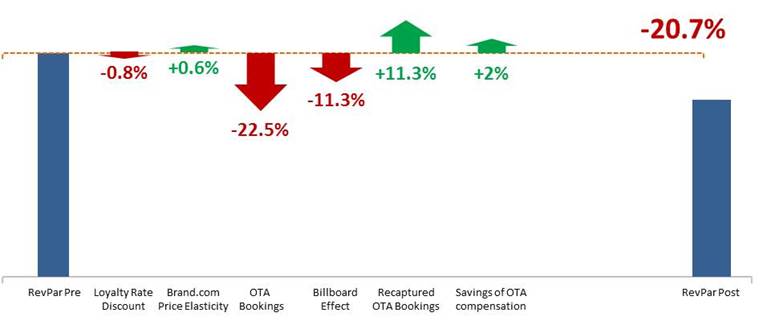

Assessment of a more European scenario, in which it’s the OTA who sells three times more

Expedia’s scenario reflects the proportion of the large North-American hotel chains, to whom the message was directed to.  How would it result if it adapted its calculations to a situation in which OTAs sold three times more than the hotel website?

How would it result if it adapted its calculations to a situation in which OTAs sold three times more than the hotel website?

According to Expedia: -20,7%

If we applied this logic and Expedia’s mathematical calculations to this other scenario, the common one for independent hotels or in European countries, the result would be an absurd -20.7%.

According to Mirai: +4,2%

In this scenario, we would also have to add another essential benefit: moving bookings to the hotel website. A situation in which OTAs sell so much is oppressive and dangerous, since the hotel would depend too much on an external channel. Solving this situation would become problem for the hotel’s sustainability and independence, despite it not being measurable in the short term in net RevPAR.

Distribution is a complex field, as is managing hotel profitability. When someone from Expedia stated that the hotelier should not take care of the distribution, perhaps they should have been more coherent and continued their logic: Only the hotelier should take care of optimising his hotel’s profitability.

Great article!

Love your content here.