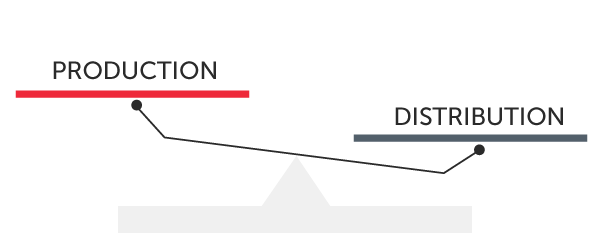

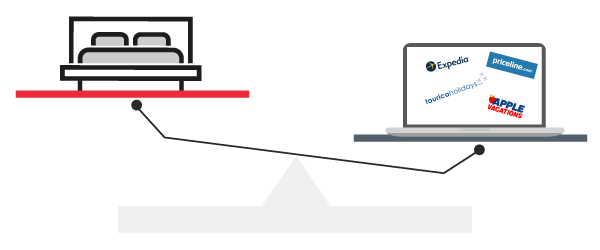

The uneven relationship between distribution and producer

Distribution has always dominated its relationship with the producer. Macy’s, Marks & Spencer and Amazon are what Tourico, GTA and, lately, Expedia are in the hotel industry. Meanwhile, the product’s owner, in our case the hotel, sees its profits increasingly reduced without knowing what to do about it.

The keys to the distributor’s success are not easy to replicate yet still simple:

- Volume or scaling to dilute fixed costs as well as gaining negotiating power to reduce unit costs.

- Large technological investment.

- Presence in the best showcases (visibility), something unreachable for producers.

- Constant pressure on its producers to increase their distribution margins and guarantee the inventory.

- Maximising income (retail price revenue management, playing with their own profits), for which being able to set the final sales price is key.

- Strong control that the product will not sell on another channel at a lower rate (parity check) and react in the event that it does happen.

Today, most producers depend on distribution to make sales. However, there are cases like Dell or Zara that show us otherwise, although this isn’t exclusive to large companies since there are many small brands who have also achieved it.

Also, there are many hotel chains who have managed to reduce their dependence on intermediaries and hundreds of independent hotels are following suit. They have fought and found a relationship with distribution which is much more balanced and profitable for their interests.

On equal terms, the big fish always wins

Many years ago, the hotel industry accepted the “inventory parity” and “rate parity” strategies in the online world. Back then it seemed reasonable and many people think it still is today. Everyone will face the same conditions and may the best man (or channel) make the most sales. What has happened since? Large OTAs and, in holiday destinations, large bed banks (who mostly sell on the Internet) ate almost the whole pie. What happened to profits? Weren’t hotels going to make more money with the arrival of the Internet? Where does that leave direct sales?

Hotels are still following the same path that small businesses took in their struggle against large-scale distribution and, of course, are obtaining the same results.

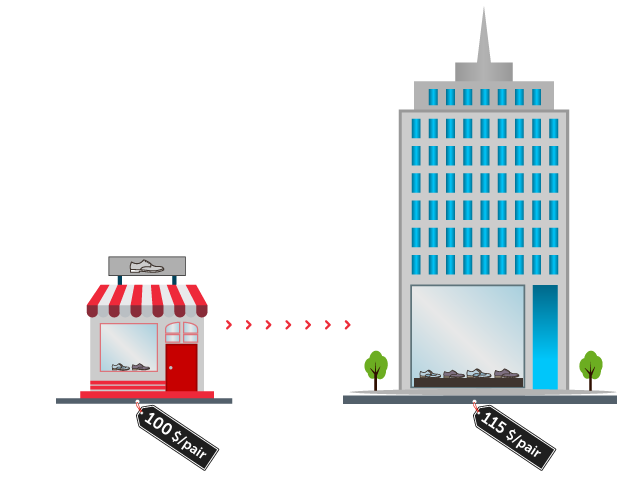

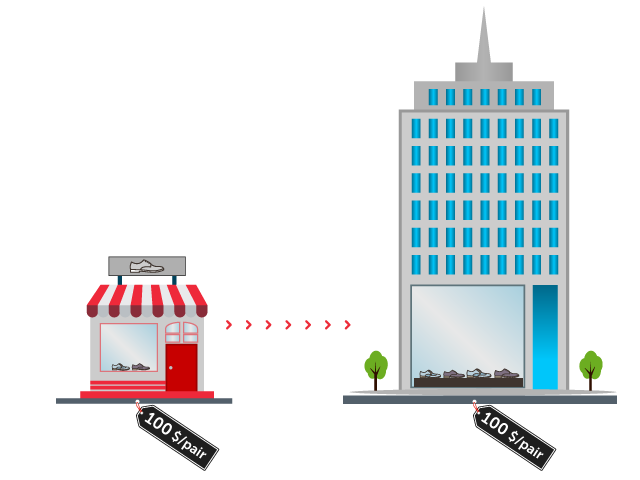

The neighbourhood shoe shop who fought against Macy’s

A famous shoe manufacturer has his shop in the city centre. He only makes 50 pairs per day and sells each of them for 100$. In order to sell more pairs, he reached an agreement with Macy’s and also distributes them there for 100$. After many years, he realises that most of his sales come from Macy’s and he barely makes any in his shop, where he previously had some degree of success. This is making him earn less money, since the commission he has to pay is very high.

After analysing the causes, he realises what is happening:

- It is a single shop against many, which, on top of it all, are located in the best streets in the city.

- He opens only 10 hours a day, 5 days a week against stores that are open 24/7.

- He speaks 2 languages, if that, and is up against a store that speaks 20.

- His return policy allows only in-store credit, whereas the other store refunds the money.

- He only accepts payment on the spot, whereas the other store allows payment in instalments.

- He accepts Visa and MasterCard only, whereas the other store accepts 12 different credit cards.

- He doesn’t publicise his store whereas the other one appears on TV, catalogues and billboards.

He therefore decides to go to work: he extends his opening hours in order to receive more clients, pays for advertising throughout the city, hires multilingual staff, reaches an agreement with the bank in order to accept Amex and UnionPay -which will bring in many Chinese customers- and, lastly, boosts his presence in social media, where they tell him there are many potential clients looking.

The results improve, although not as much as he expected. However, what have really grown are his expenses. In fact, when he works out the figures, his direct-sales costs have shot up so much that it shocks him and somewhat paralyses him. He realises that he is competing against a department store like Macy’s, which is considerably superior (in technology and investment power) and against which there is nothing he can do.

After many years enduring this, he ends up frustrated and considers giving up.

What if we deal with this problem at the root? The inventory

Fed up of fighting a war that isn’t his to fight, the owner decides to question a mantra that, up until now, was taboo: inventory and rate parity.

He decides to increase the price of his famous shoes in Macy’s to 115$, therefore forcing the client to make a decision which previously was very easy: make an effort to go to the shop, as uncomfortable as that may be, or pay more and maintain the comfort of going to Macy’s? He’s surprised by how sales in his shop shoot up from one day to the other.

Many clients go there for the discount but, above all, his online sales are the ones that particularly shoot up. He realises that a lot of the sales were made by Macy’s on the Internet. He barely got any!

While on a roll, he takes it a step further. He knows that on dates like Christmas or sales, he always sells the whole of his inventory easily. That is when he needs Macy’s the least. He has two options:

- Increase the rate he charges Macy’s, at the very least to the point that the profit is the same as his direct sales.

- Sell the product exclusively in his shop despite that, in order to achieve this, he will have to invest in advertising to make it known.

This is how he finds the formula and ends up making a lot more money. He realises that many clients still go to Macy’s and don’t buy his shoes -whether it’s because they are more expensive or simply because they don’t have any- but, since they are dates of high demand, it doesn’t worry him because he sells all of his inventory anyway.

The best strategy to compete against OTAs involves managing inventory appropriately

Obviously, the aforementioned shoe shop is in fact the hotel and Macy’s represents the crushing dominance exerted by OTAs. Just like the shoe shop, hotels don’t have any chances when competing against OTAs in terms of investment, technology, visibility and even brand. Keeping up with SEO, SEM, meta-search engines, web improvements, languages, price-comparison widgets, programmatic marketing, etc. is a wild-goose chase, a huge expenditure and it generates frustration and decrease in profitability.

Hotels must understand that there is only one thing they have

that distributors don’t: the rooms.

In other words, without your rooms, distributors cannot do anything, no matter how much money they have. Not having inventory and having to depend on hotels is the Achilles heel of distribution.

Today, the fight is not even in the rate, like it used to be years ago. Many hotels are aware that the last room is sold on OTAs, at a higher rate even than on their own website. Hotels that work with tour operators know that, this year, rates are not as important and that what they look for is guaranteeing a number of beds. Much to our regret, large OTAs like Booking.com and Expedia are selling despite not having the best rate and, worst of all, this trend is increasing. If we carry on like this, where will we be in 5 years’ time?

The main duty hotels have is to acquire the know-how that will allow them to maximise profits from their most prized asset, the only thing that sets them apart from distributors: their rooms. They must decide where and at what price they are going to sell rooms on each of the channels, burying the mantra of “inventory and rate parity” once and for all.

Enemies against breaking inventory parity

In order to eliminate inventory parity, hotels need to overcome obstacles that are not always clear:

- Technology. There is a clear functional deficit with channel managers that makes inventory management impossible. You must choose a channel that will allow you to segment your inventory and manage it differently for every channel and depending on the business rules. You must eradicate the regular configuration for many two-way shared-pool channel managers, since it benefits the channels who sell more in advance (tour operators, bed banks and OTAs, in that order). An example of an action to configure on a channel would be the following: close Hotelbeds, increase Expedia by 8% and Booking.com by 4% as well as add 3 nights’ minimum stay on a specific date when occupancy reaches 60% and the advance-booking time is more than 30 days.

- Knowledge of channel and their advance sales. Anticipating those less-profitable channels who sell well in advance is key, since they are consuming rooms that you will later miss. For this, you need support from your PMS in order to properly understand which channels sell which months, how long in advance and the profitability they make. Without this information, you cannot even begin to make decisions.

- Eradicate the famous “cushion”. If a date is popular and you’ve filled it for the past 10 years, and could’ve even filled the hotel twice over, don’t be afraid to select the channels through which you want to fill that date from day 1 and don’t even open the less profitable and darker ones (those that can’t guarantee that control over the retail price, usually bed banks). If you wait until you have the traditional “cushion”, you’ll end up missing those rooms when you increase room rates.

- Leaving your comfort zone. Making hard decisions isn’t easy. It implies determination and understanding that intermediaries won’t make it easy for you (fear, threats, straining the relationship…). Finding that new balance that will make your profits shoot up won’t be easy but it’s the only option left if you want to regain control of your distribution.

- Non-aligned incentives. If the one to lead this distribution-model change in your hotel with the objective of increasing profitability (net RevPAR) doesn’t have a clear and common incentive, it won’t work. In other words, if your manager or revenue manager doesn’t earn more with all of this extra work he has to do, he’ll end up not doing it and returning to the comfort zone. Why work double if I’m not making more money?

- Breaching contracts. Many contracts with distributors have rate-parity clauses which, although forbidden throughout most of Europe, are still in force in Spain (are we fools?). In the same way that intermediaries do not respect contracts (for example, the famous and hypocritical “binding rates” of affiliations and bed banks), you will have to selectively breach many contracts in order to newly reorder your distribution.

Conclusion

If we are to compete against distributors on a level in which they are far superior, we are destined for failure. The large amounts of money that they assign to SEO, SEM (brand or generic) or meta-search engines confirms that the focus is still wrong. For now, few hotels understand that inventory management is the best strategy -since it’s the most effective one and it requires less investment yet also analytical skills, knowledge of how distribution works and diplomacy in order to find a balance in the relationship with the distributor- or as an alternative, price adjustment so that each channel covers their different distribution costs, although that’s something we should discuss in another post.

David didn’t need an army to defeat Goliath. Just like he had a sling, you have your precious inventory. It’s an uneven fight but it’s in your hands that you fight it intelligently.

Im really enjoying your posts and especially love the Macy’s analogy a lot. I would go one further however and argue that there are many retailers that recognize distribution/retail isn’t their forte and focus on the product, brand, customer engagement etc (think food retail) however I do concede they in these instances they typically have exceptionally high sales volumes.

What I don’t agree with is your suggestion to restrict inventory from specific channels on specific dates. The OTA’s algorithms are designed to reward consistent inventory so by being restrictive you run the risk of paying proportionately more on the dates when you need the OTA, which is counter productive.

The articles coming from Mirai, like this one, are brilliant. I have no affiliation with them, but I nevertheless send out each one to my entire team. Keep up the great work! Your insight is making a meaningful difference for hoteliers all over the world.